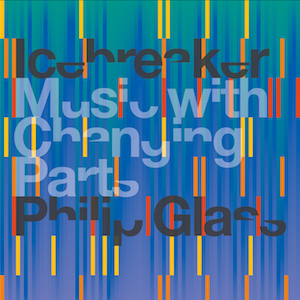

Music with Changing Parts

1. Music with Changing Parts I - Philip Glass

2. Music with Changing Parts II - Philip Glass

Orange Mountain Music OMM 0035

Buy from:

iTunes

Amazon

2. Music with Changing Parts II - Philip Glass

Orange Mountain Music OMM 0035

Buy from:

iTunes

Amazon

Many composers have, somewhere in their back catalogue, pieces that can be thought of as sleepers – works that after an initial period of performances fall into obscurity, only to be unearthed years or even decades later, often revealing themselves as undiscovered masterpieces. Such a case could certainly be made for Philip Glass’s Music with Changing Parts, composed in the summer of 1970. This work featured in concerts by the Philip Glass Ensemble for several years, one of which was recorded in New York in 1971 for Glass’s Chatham Square label. But the piece then faded from the ensemble’s ongoing repertoire at the beginning of the 80s, after which it remained unperformed for some twenty-five years. This is not entirely surprising: after all, no ensemble could keep in performance all of the astonishing quantity of music Glass has composed for his small band of musicians in the years since 1968. The recording went out of print in the late 70s; it was reissued on CD by Nonesuch in 1994. But still there were no live performances.

So it was that, given the invitation to programme a work of Glass at a concert at London’s Tate Modern in July 2005, Icebreaker’s artistic director James Poke found himself intrigued by this lesser-known piece, whose intricate, interweaving lines and mesmeric rhythmic swirl, together with its lack of prescribed instrumentation, made it seem perfect for the high-energy approach of Icebreaker. Glass offered to have his manuscript copied into more legible form, enabling Music with Changing Parts to come back to life – and to take its rightful place as one of the most important, as well as one of the most ravishing, products of the first period of its composer’s work. For many listeners, this new recording may be a first encounter with one of Philip Glass’s most important pieces.

In the chronology of Glass’s output Music with Changing Parts comes immediately after early works like Music in Fifths, Music in Contrary Motion and Music in Similar Motion (all dating from 1969) and before established classics like Music in Twelve Parts (1971-74) and the opera Einstein on the Beach (1975-76). The initial spark for the work came from a rehearsal of Music in Similar Motion in a beautifully reverberant wooden theatre in Minneapolis in May 1970. Glass recalls that, rehearsing the end of the piece, he heard a sound that wasn’t in the score, like the sound of someone singing. Thinking one of the musicians was fooling about, he stopped and looked around; but everyone had been continuing to play as normal. When they resumed he found that he could still hear the sound, and realised that what he had been hearing was a psychoacoustic effect caused by the reverberant space – an audible phantom that resembled the sound of a human voice. This gave him the idea of using a wordless voice in his next piece, which was to be Music with Changing Parts. In keeping with the unpredictable nature of this Minneapolis experience, the players in this piece are permitted to contribute improvised long tones in places, instead of playing the written parts: this adds a degree of spontaneity into the music that was a new development in Glass’s work of that time.

Music with Changing Parts is flexible in instrumentation: the smallest possible ensemble realisation would need four keyboards. Performances of the work by the Philip Glass Ensemble likewise varied somewhat. Seven musicians were featured in the version they recorded in 1971, but most of them doubled on at least one other instrument, so that the full instrumentation involved flutes, piccolo, alto flute, soprano and tenor saxophones, trumpet, electric violin, electric piano and electric organs; in addition, four of the musicians also contributed vocal tones, making the overall sonority the richest Glass had created to that point. In reviving the work in 2005, Icebreaker’s musical director Richard Craig faced a choice: whether to try to recreate the soundworld of the Philip Glass Ensemble of the early 70s or to reconceive the piece in their own terms. Deciding the former was essentially impossible and in any case pointless, they opted for the latter, and worked out a distribution of the music for their full cohort of thirteen players and with an instrumentation of panpipes, flute, wind synthesizer, saxophones, bass clarinets, voice, keyboards, electric violin, cello, electric guitar, bass guitar and marimba.

This sort of flexibility is inherent in the nature of Glass’s score. The music is laid out in four pairs of staves, so that there is a maximum of eight different musical lines happening at once (not counting the sustained tones). Any instrument or voice can play any line, and more than one player may play the same line. The musicians are expected to breathe and rest when they feel the need. This allows for an essentially unlimited variety of tone colour, as players move in and out of the texture or change from playing rhythmic patterns to long tones and back again. The piece consists of a total of seventy-six different repeating patterns of varying lengths, each of which may be repeated as often as the musicians wish – in performance, cues (usually in the form of nods) are given to signal a move from one pattern to the next. Some of the individual patterns are as brief as four notes, others as long as forty-eight. Most of them are a different length than the immediately preceding pattern, and have a different internal rhythmic structure, such that the changes from one to the next create an overall rhythmic flow that never becomes predictable. (In fact Glass’s skill at sustaining this unpredictability over such a long time-span is one of the most brilliant achievements of Music with Changing Parts.) The work as a whole falls into two large parts, the main difference being a rhythmic one: in Part I the patterns are built from groups of two notes, whereas in Part II they are built from combinations of groups of two and groups of three. Yet for all the emphasis on a rigorous and ingenious structure propelled largely by rhythmic means, perhaps the most significant innovation in Music with Changing Parts is the creation of the first genuinely harmonic textures in Glass’s output thanks to the use of sustained tones. In earlier pieces such as Two Pages or Music in Similar Motion, harmony was implicit in the repeated melodic patterns rather than actually sounded. This new emphasis gives the music a warmth that makes it distinct from the greater austerity of these immediately preceding works, and points the way forward to the orchestral textures of Glass’s more recent work.

The result is a classic of its era, a work that inhabits new musical territory somewhere between “classical” and “popular” musics, exuberantly manifesting the discipline and the emphasis on large-scale structure characteristic of the former and the sensuousness, vitality and sheer volume of the latter. One of the Philip Glass Ensemble’s early performances of Music with Changing Parts, at London’s Royal College of Art in March 1971, seems in retrospect highly prophetic of what was to come: among the audience were David Bowie and Brian Eno, still at the beginning of their own careers, both loving what they heard. (Glass would return the compliment by basing his “Low” Symphony and his “Heroes” Symphony on their music two decades later.) The fact that Icebreaker’s revival of Music with Changing Parts should come at the request of Tate Modern, rather than a concert hall, continues an honourable tradition. And it is a testament to the music’s staying power that the audiences for Icebreaker’s performances have been as young as those for the Philip Glass Ensemble’s performances a quarter of a century earlier. Having been a “sleeper” for much of that intervening time, Music with Changing Parts is now well and truly awake.

Bob Gilmore

So it was that, given the invitation to programme a work of Glass at a concert at London’s Tate Modern in July 2005, Icebreaker’s artistic director James Poke found himself intrigued by this lesser-known piece, whose intricate, interweaving lines and mesmeric rhythmic swirl, together with its lack of prescribed instrumentation, made it seem perfect for the high-energy approach of Icebreaker. Glass offered to have his manuscript copied into more legible form, enabling Music with Changing Parts to come back to life – and to take its rightful place as one of the most important, as well as one of the most ravishing, products of the first period of its composer’s work. For many listeners, this new recording may be a first encounter with one of Philip Glass’s most important pieces.

In the chronology of Glass’s output Music with Changing Parts comes immediately after early works like Music in Fifths, Music in Contrary Motion and Music in Similar Motion (all dating from 1969) and before established classics like Music in Twelve Parts (1971-74) and the opera Einstein on the Beach (1975-76). The initial spark for the work came from a rehearsal of Music in Similar Motion in a beautifully reverberant wooden theatre in Minneapolis in May 1970. Glass recalls that, rehearsing the end of the piece, he heard a sound that wasn’t in the score, like the sound of someone singing. Thinking one of the musicians was fooling about, he stopped and looked around; but everyone had been continuing to play as normal. When they resumed he found that he could still hear the sound, and realised that what he had been hearing was a psychoacoustic effect caused by the reverberant space – an audible phantom that resembled the sound of a human voice. This gave him the idea of using a wordless voice in his next piece, which was to be Music with Changing Parts. In keeping with the unpredictable nature of this Minneapolis experience, the players in this piece are permitted to contribute improvised long tones in places, instead of playing the written parts: this adds a degree of spontaneity into the music that was a new development in Glass’s work of that time.

Music with Changing Parts is flexible in instrumentation: the smallest possible ensemble realisation would need four keyboards. Performances of the work by the Philip Glass Ensemble likewise varied somewhat. Seven musicians were featured in the version they recorded in 1971, but most of them doubled on at least one other instrument, so that the full instrumentation involved flutes, piccolo, alto flute, soprano and tenor saxophones, trumpet, electric violin, electric piano and electric organs; in addition, four of the musicians also contributed vocal tones, making the overall sonority the richest Glass had created to that point. In reviving the work in 2005, Icebreaker’s musical director Richard Craig faced a choice: whether to try to recreate the soundworld of the Philip Glass Ensemble of the early 70s or to reconceive the piece in their own terms. Deciding the former was essentially impossible and in any case pointless, they opted for the latter, and worked out a distribution of the music for their full cohort of thirteen players and with an instrumentation of panpipes, flute, wind synthesizer, saxophones, bass clarinets, voice, keyboards, electric violin, cello, electric guitar, bass guitar and marimba.

This sort of flexibility is inherent in the nature of Glass’s score. The music is laid out in four pairs of staves, so that there is a maximum of eight different musical lines happening at once (not counting the sustained tones). Any instrument or voice can play any line, and more than one player may play the same line. The musicians are expected to breathe and rest when they feel the need. This allows for an essentially unlimited variety of tone colour, as players move in and out of the texture or change from playing rhythmic patterns to long tones and back again. The piece consists of a total of seventy-six different repeating patterns of varying lengths, each of which may be repeated as often as the musicians wish – in performance, cues (usually in the form of nods) are given to signal a move from one pattern to the next. Some of the individual patterns are as brief as four notes, others as long as forty-eight. Most of them are a different length than the immediately preceding pattern, and have a different internal rhythmic structure, such that the changes from one to the next create an overall rhythmic flow that never becomes predictable. (In fact Glass’s skill at sustaining this unpredictability over such a long time-span is one of the most brilliant achievements of Music with Changing Parts.) The work as a whole falls into two large parts, the main difference being a rhythmic one: in Part I the patterns are built from groups of two notes, whereas in Part II they are built from combinations of groups of two and groups of three. Yet for all the emphasis on a rigorous and ingenious structure propelled largely by rhythmic means, perhaps the most significant innovation in Music with Changing Parts is the creation of the first genuinely harmonic textures in Glass’s output thanks to the use of sustained tones. In earlier pieces such as Two Pages or Music in Similar Motion, harmony was implicit in the repeated melodic patterns rather than actually sounded. This new emphasis gives the music a warmth that makes it distinct from the greater austerity of these immediately preceding works, and points the way forward to the orchestral textures of Glass’s more recent work.

The result is a classic of its era, a work that inhabits new musical territory somewhere between “classical” and “popular” musics, exuberantly manifesting the discipline and the emphasis on large-scale structure characteristic of the former and the sensuousness, vitality and sheer volume of the latter. One of the Philip Glass Ensemble’s early performances of Music with Changing Parts, at London’s Royal College of Art in March 1971, seems in retrospect highly prophetic of what was to come: among the audience were David Bowie and Brian Eno, still at the beginning of their own careers, both loving what they heard. (Glass would return the compliment by basing his “Low” Symphony and his “Heroes” Symphony on their music two decades later.) The fact that Icebreaker’s revival of Music with Changing Parts should come at the request of Tate Modern, rather than a concert hall, continues an honourable tradition. And it is a testament to the music’s staying power that the audiences for Icebreaker’s performances have been as young as those for the Philip Glass Ensemble’s performances a quarter of a century earlier. Having been a “sleeper” for much of that intervening time, Music with Changing Parts is now well and truly awake.

Bob Gilmore